Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs), and Language Models (LMs) in general, facilitate a new way of programming in which “instructions” are no longer unambiguous APIs but are statements in a natural language like English. Experts in this space, a new area known as prompt engineering, program their LMs—or elicit specific behaviors from them—by combining particular keywords, prompt formats, and even cognitive models.

The past two years have demonstrated that LMs can be widely transformative but carry inherent limitations in integrating seamlessly into larger program environments. They have imperfect memory of facts and prior interactions, cannot reliably adhere to logical structures, cannot interact with external environments or execute computations, and are sensitive to the ways in which they’re prompted. To address these limitations, over a dozen popular frameworks have emerged, favoring different philosophies for abstracting interactions with and between LMs.

This article provides the most comprehensive review of these frameworks to date, under a more systematic taxonomy than existing discussions. Beyond providing a map of the landscape of frameworks for abstracting interactions with and between LLMs, this article additionally provides two systems of organization for reasoning about the various approaches and philosophies to abstraction:

- Language Model System Interface Model (LMSI), a new seven layer abstraction, inspired by the OSI model in computer systems and networking, to stratify the programming and interaction frameworks that have emerged in recent months. These layers are presented in order from highest-level abstraction layer to lowest-level abstraction layer in the overall stack of LM abstractions.

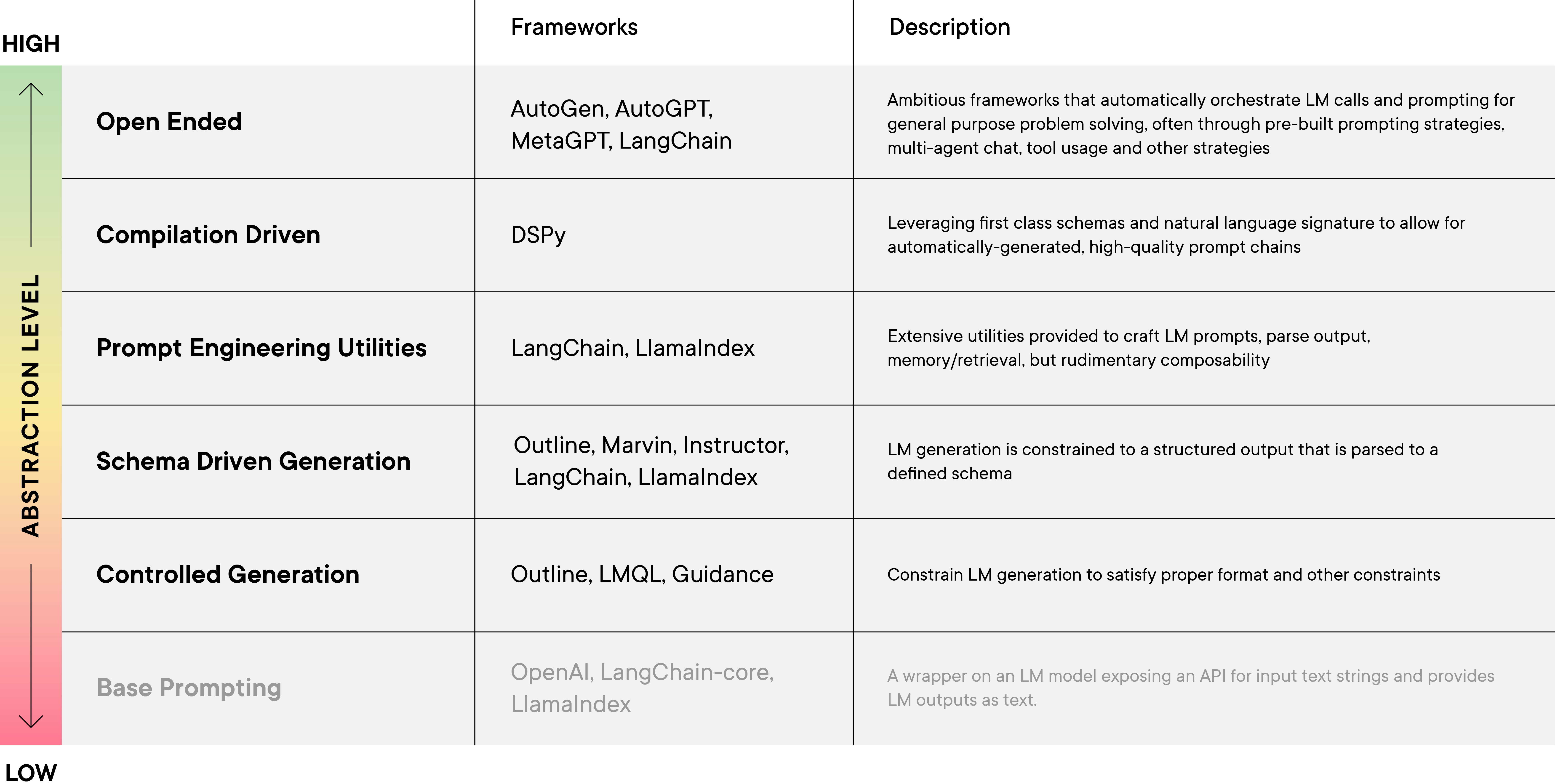

- A categorization of five Families of LM Abstractions which we have identified to perform similar classes of functionality in our review. These categories group libraries roughly occupying the same layers and are presented in rough order from higher- to lower-level of abstraction.

The two systems of organization—the Language Model System Interface Model (LMSI) and the categorization of Families of LM Abstractions—are interconnected through their approach to abstraction levels. The arrangement of the LM abstraction families follows a spectrum, roughly corresponding to the LMSI model’s abstraction layers– in particular, it attempts to describe the level of detail exposed to the user or developer. For example, at one end of the spectrum, lower-level abstractions involve direct interaction with the LLM’s parameters through Python functions (e.g., at the LMSI’s Neural Network Layer). On the opposite end, higher-level abstractions provide tools for prompt generation and optimization, enabling recursive refinement of the LLM’s responses without delving into the underlying technical complexities of the underlying LLM or pipeline (e.g., at the LMSI’s Optimization Layer or Application Layer).

The remainder of this article can be read together or separately. In the first section, we introduce the LMSI, define the layers, and attempt to show how each of the LM frameworks we examine lays across various LMSI layers, before we describe each framework in detail. In the second section, we introduce the five families of LM abstractions, where each category roughly represents an approach to providing LM abstractions to users or developers. We go into detail on what each category covers, and it is here that we describe most frameworks we have examined in more detail, including code examples demonstrating what it should look like to use and interact with many of the frameworks across the five categories.

Language Model System Interface Model (LMSI)

Over the course of our examination of LM frameworks, we observed a trend; we could broadly identify specific frameworks as higher-level, lower-level, or at mixed-levels of abstraction. However, exactly what “high” or “low” meant in this context remained unclear without further organization.

Inspired by the OSI model from computer systems and networking, we developed a notion of different functional layers that these frameworks could focus on, and, importantly, they could easily be organized from high- to low-level in the stack of LM libraries and frameworks. In all, we identified seven layers of abstraction that LM frameworks can typically operate at/expose to users. The layers denote increasing levels of abstraction, starting from directly interacting with the architecture, weights and parameters of an LM– the lowest level of abstraction, i.e. the Neural Network Layer, to the highest level of abstraction, or, treating LM-enabled applications as a black-box for general high-level user-provided tasks, i.e. the User Layer.

We believe that, beyond achieving the goal of organizing/classifying existing LLM abstraction frameworks, these layers can help to identify where different emphasis and features for an LLM framework could be uncoupled from one another. Like in the case of the OSI model, we hope the stratification into layers could provide clarity to framework developers vis-à-vis designing their abstractions at the right level to possibly leverage existing infrastructure already implemented in other frameworks– effectively separating concerns and allowing frameworks to offload expertise to other frameworks at abstraction boundaries/interfaces. At the current stage, however, whilst many frameworks fall into narrow bands of layers, some span a broader segment, often reflective of an expansive design where high-level abstractions can interact with low-level features in a way that is exposed to developers.

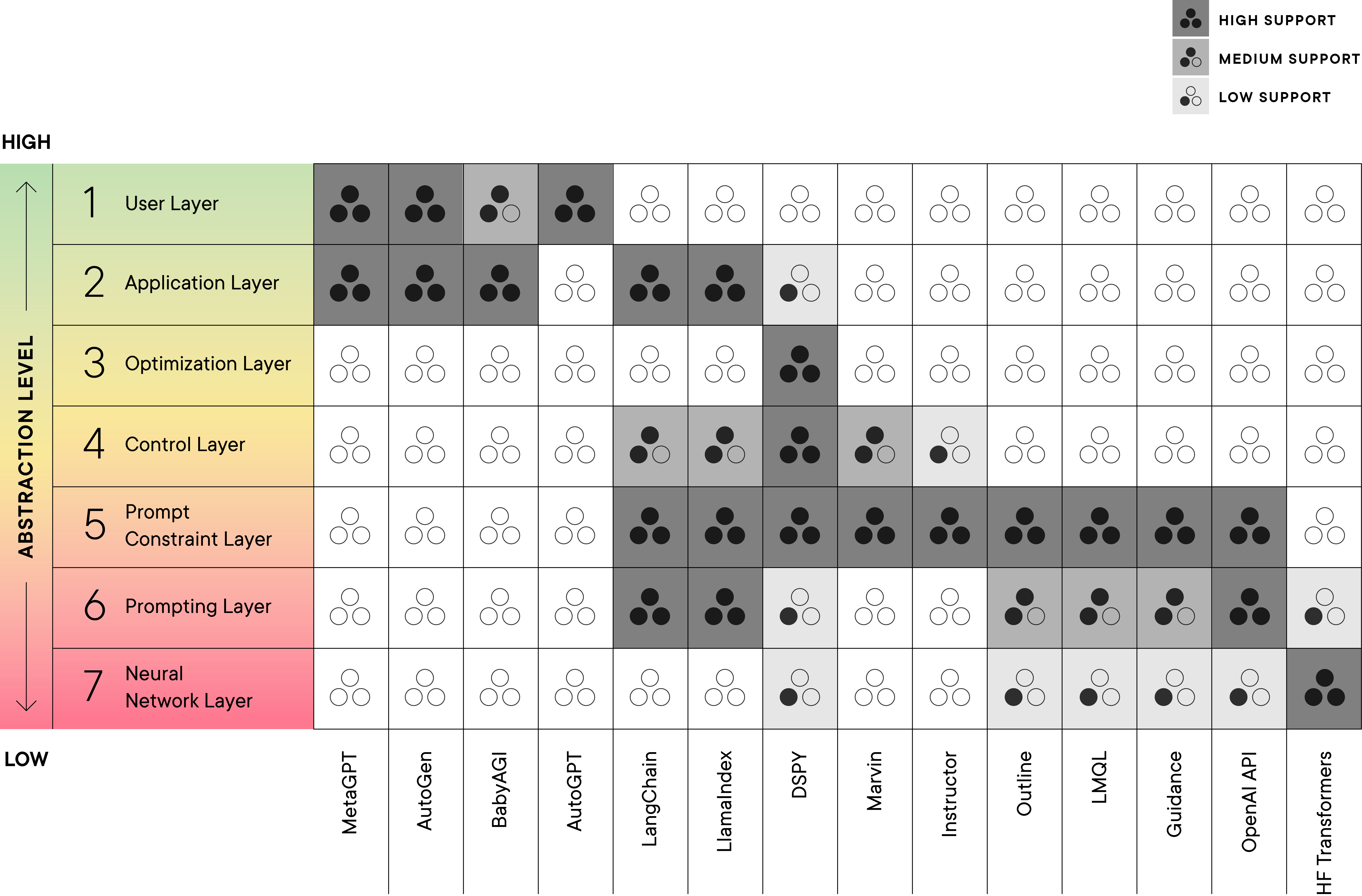

The list below contains a description and definition for each layer, while Table 1 represents the layer(s) and the emphasis recent frameworks place on a given layer, represented through the stars.

- Neural Network—Directly access the architecture and weights/decoding component of the LM.

- Prompting—Input of text to a LM via API, manual chat, or other interface, possibly without limitations on the input or output text sequences.

- Prompt Constraint—Imposition of rules or structures across groups or types of prompts (for instance through templating), or constraints and validation of the output.

- Control—Control flow support such as conditional, loops, dispatching supported in the framework.

- Optimization—Optimize some aspect of the LM or system of LMs based on a metric.

- Application—Library, utilities and application code that build on lower layers that provide general out-of-the-box solutions with some configurability.

- User—Human interaction layer where the application is directly interacting with human directives to perform LM powered tasks.

Five Families of LM Frameworks

Rather than describing each framework in isolation in order of abstractions, we have identified a few categories of libraries performing similar functions that have emerged in our review. These categories group libraries roughly occupying the same LMSI layers and are presented in roughly increasing order of abstraction.

The first group of frameworks are those focused on Controlled Generation (like Guidance and LMQL). These frameworks make it possible to define formatting requirements and other constraints on the outputs of LMs (e.g., via regular expressions), which is a key ingredient for building reliable systems around LMs. Building on this foundation, libraries for Schema-Driven Generation (like OpenAI’s Function Calling mode and Marvin) allow users to express type-level output structures (e.g., as Pydantic schemas). Leveraging the powerful abstractions of schemas and natural language signatures, frameworks, spearheaded by DSPy, focus on the Compilation of LLM Programs, revolve around compiling programs (where LLM calls are a first-class construct) into automatically-generated, high-quality prompt chains. The compilation-driven strategy is distinct from Prompt Engineering Tools with Pre-Packaged Modules, such as LangChain and LlamaIndex, where a collection of pre-packaged utilities for generating and parsing prompts, along with rudimentary primitives for connecting the generated response with other LM calls or environmental calls, can be used to interact with LMs in a more meaningful manner. Such tools, at their core, however, are still relying on manual prompt engineering techniques. At the highest level, we discuss the most ambitious Open-Ended Agent frameworks (like AutoGPT and MetaGPT) and the Multi-Agent Chat paradigm (like in CAMEL and AutoGEN).

0) Base Prompting

The lowest-level we hesitate to include in our families of LM frameworks is the state-of-the-art prior to the advent of abstraction frameworks for LMs; Base Prompting.

Base Prompting simply describes what users have always been able to without any additional framework, given an LM or API to an LM Base Prompting can be thought of as simple wrappers around different LMs that express their most primitive interface (text in, text out) in a uniform way. This is the core of the OpenAI (and other providers’) APIs as well as some of the main abstractions in the LangChain-core package. For some applications, this raw form provides sufficient flexibility to build hand-crafted prompts or to build higher-level abstractions.

1) Controlled Generation

LMs complete text in a statistically likely but non-deterministic way. This means that LM responses can be unpredictable, making it difficult to integrate into other workflows. A class of libraries mitigate such concerns by applying template or constraint-based controlled generation techniques, exemplified by Outlines, Guidance and LMQL. These libraries utilize a templating engine where the templates express prompts with “holes” for the generation to fill. The generated content from these LMs can be bound to template variables and substituted into subsequent generations, guiding their outputs. These libraries also support constraining the outputs to restrictions such as subset membership, schema, and length. LMQL takes advantage of the decoding component of an LLM to achieve such filtering, while Outlines modifies the LM’s ability to modify token probabilities to support output constraints. These frameworks tend to span between the Neutral Network Layer to the Prompt Constraint Layer.

LMQL programs are expressed in a domain specific language (DSL) embedded in Python (See Example 1) where top-level strings, which may contain “holes” represented by square brackets with optional type annotations, are prompts used for completion and additional constraints are represented by where statements. LMQL introduces the notion of an eager and partial evaluation semantic, which conservatively approximates whether or not a constraint will hold for a particular generation. Using this semantic, LMQL can generate a model-specific token mask to prune the search space during the decoding process.

Outline has a similar capability to efficiently guide generation with regex, which can also support many of the constraints supported by LMQL. Internally, Outline formulates neural text generation as transitions between states of a finite state machine. It builds up an index over the model’s vocabulary and can efficiently guarantee the structure of the generated text by manipulating the model probabilities on the tokens. The library also has many built-in features that build on the idea of CFG-guided generation for more practical usage such as prompt generation using the Jinjia templating language or object type constraints and schema using json and Pydantic.

However, in the case of LMQL, access to the decoding component of an LM may not be readily available for hosted endpoints like GPT-3 and GPT-4. Further, some of the “fill-in-the-blank” strategies used by these libraries are more suitable for LMs designed for completion, as opposed to Chat, which is not the case for GPT-4, for instance.

2) Schema-Driven Generation

A more refined abstraction for controlled generation is schema-driven generation. Here, the boundary between the LM and its host programming interface is constrained by some predefined schema, or some object specification language (typically JSON). This is different from Guidance and LMQL, where the user must specify the JSON skeleton and its internal content restrictions if they wish for a JSON output. Compared to controlled generation, a schema-based approach could be more easily integrated to other existing programming logic. However, the granularity of control over the type of content generated could be more limiting. These libraries are placed in the Prompt Constraint Layer since conformance to a schema is a way to limit the output of the LM.

In Outlines, other libraries such as Marvin and Instructor, and more recently in LangChain and Llamaindex, this step is abstracted further. Users could specify a data structure using the data validation library Pydantic as the output schema for certain LMs (Model-level abstraction). Internally, these libraries encode the schema as natural language instructions through Prebuilt Prompts requesting the LMs to output in the correct, parsable formats. However, for Marvin and Instructor, there is some support to leverage more advanced features provided by the underlying LLM vendor (e.g. Function Calling by OpenAI to enforce parsability). OpenAI’s new JSON mode is also expected to be adopted by these libraries to reduce the likelihood that the output is unparsable.

Instructor, for instance, provides an alternative client for OpenAI APIs that accepts a response model specified using Pydantic as shown in (Example 2). In its implementation, it supports three modes of querying the LM, namely json, function calling, and tools usage, each corresponding to the equivalent OpenAI supported APIs. To guide the LM in this parsing process, Instructor has some internal prompts to instruct the LM of the schema and the output format.

In LangChain, there is support for more sophisticated retry parsers when validation errors do occasionally occur, but the outputs are prompted not through the function calling API from OpenAI but more through natural language instructions.

In (Example 3), LangChain’s parsing and retrying process is examined in more detail. This example reflects LangChain’s greater emphasis on string and prompt manipulation and shows some of the more ad-hoc but helpful tools they provide.

Beyond output data schemas, some libraries have added support for functional schemas(Function Level Abstraction) in the context of LLM interactions by allowing programmers to declaratively annotate functions with a natural language schema or signature, representing their high-level intents. This idea first appeared in the DSP project in early 2023, which served as the precursor to the DSPy framework. In DSP, users could specify the Type of a function’s inputs and outputs(in the most simple case : “Question, Thoughts -> Answer”) which consisted of a human-level description of what the parameter entailed and the relevant prefix. The collection of input and output Types formed a DSP Template, where a callable Python function could be induced. Marvin has more recently streamlined this pattern through its “AI Function”, where the programmer’s annotation of input and output types and function doc strings is used to generate a prompt based on some runtime inputs to extract an output from the LM.

(Example 4) describes the Marvin AI functions. Here, the annotated function will be intercepted at runtime, where the Python type signature, description, and input are all fed to an LM to extract an output. The type hints are used as a validator to maintain type safety. The abstraction also allows a natural language invocation of the function.

In DSPy, developers can similarly specify the Natural Language Signature to declaratively define some (sub) task that the LLM needs to solve, induced from a short description of the overall task and the descriptions of the input and output fields.

(Example 5) shows how DSPy leverages Natural Language Signatures to create LM powered functions adhering to a given signature.

3) Compiling LM Programs

The concretization of a natural language specification of a function can vary in a large search space, depending on the examples provided (e.g. few-shot vs zero-shot), prompting strategies (e.g. chain-of-thoughts), external data source (RAG), or even a multi-hop approach (e.g. program-of-thoughts). In Marvin, the concretization strategy is rigid and developers are generally constrained to using the out-of-the-box solution provided. For DSPy, however, the natural language signatures are detached from the specific querying strategy which means to use a signature, users must declare a Module with that signature. These modules may additionally take an optional list of examples (or demonstrations). DSPy also includes a number of sophisticated modules like ChainOfThought, ProgramOfThought, MultiChainComparison and ReAct that can apply these prompting or interaction strategies to any arbitrary DSPy signature without manual prompt engineering.

Continuing from (Example 5), (Example 6) shows that changing the prompting strategy can be as easy as changing the module that powers the signature.

The DSPy modules are composable in the same fashion as PyTorch using a define-by-run interface, allowing an arbitrary pipeline to be built. A powerful concept in DSPy is the ability to compile a pipeline, which optimizes it by selecting hyperparameters such as instructions/prompts or demonstrations, or even fine-tuning. This optimization process is conducted through a teleprompter, which denotes a specific optimization strategy. An example of which is the BootstrapFewShot teleprompter which bootstraps examples from a small number of inputs (note that output is not strictly needed) to the module pipelines. This teleprompter runs the pipeline on the inputs and selects the demonstrations that satisfy some customizable heuristics.

(Example 7) demonstrates how DSPy‘s compilation process works. Generally, compilation in DSPy requires a training set (Note: A testing set is not strictly required), a metric for validation (the validate_context_and_answer function), and a teleprompter, in this case BootstrapFewShot. Different teleprompters offer different optimization strategies and tradeoffs in terms of cost and quality. The modular design of DSPy means other teleprompters could be used in place without too much change in scaffolding.

Compared to other techniques, compilation-based systems offer several clear advantages such as the ability to change different prompting strategies without redefining the underlying signature, and the performance improvement through optimization. However, to reap the benefit of compilation, there is non-trivial scaffolding involved and an understanding of the underlying DSPy system is required. For projects requiring significant LM-environment interactions, or simple projects not requiring much optimizations, it may be challenging to adopt the system at this stage.

4) Prompt Engineering Utilities

A very different approach is taken by another class of libraries including LangChain and LlamaIndex where, through a myriad of pre-packaged modules, these libraries form “out-of-the-box” solutions for programs that use LMs. In contrast with DSPy, for instance, these libraries tend to have many features available, have a greater reliance on prompt engineering, and focus on a few specific interaction models with the LLM itself. LangChain, for instance, includes utilities that manage prompt templating, output parsing, memory, and retrieval model integration.

LangChain also provides prebuilt abstractions that take advantage of these utilities to offer more sophisticated modes of interacting with LMs and the external environment. The Agent and Chain abstractions, specified by LangChain’s domain specific language: LangChain Expression Language (LCEL), enhance functionality and reusability of the utilities to solve more complex tasks. Generally speaking, the LCEL allows the users to specify a set of tools or actions available to the LM to interact with some external environments and a pre-set prompt and Output Parser perform the orchestration step that determines which actions/tools to invoke and how the result of the agent is passed onto future iterations of the agent loop. LangChain provides a plethora of pre-set prompts and Output Parsers (such as for ReAct, Chain-of-Thoughts, self-ask, etc) that can aid developers in rapidly building complex agent systems suitable for many use cases. However, the LCEL mainly acts as a lightweight syntactic sugar over a simple agent loop and whilst the components are customizable, at the time of writing, they do not enable more advanced features over native implementations, and the pattern of interaction in the agent loop itself is somewhat fixed.

This example shows the LCEL in action when used to implement the Self-Ask prompting strategy. The agent variable demonstrates the usage of the LCEL to combine the prompt substitution (first element), the prompt itself, the LM used, and the Output Parser. The prompt itself (available here) has many demonstrations where the LM asks intermediate questions, along with two fields, “input” and “agent_scratchpad”, as holes for substitution. The output parser scans the generation sequence and looks for string matches such as “Follow up:” or “So the final answer is:” and depending on the generated sequence, would dispatch different AgentActions that determine which tool to invoke or whether the final result has been reached. The programmer in this case would be responsible for controlling the substitution of prompts for each loop by substituting the input and using the format_log_to_str function to create a suitable string based on the intermediate action steps to substitute into the scratchpad (essentially putting all the intermediate questions and answers returned from the tool to the prompt). In this case, even though the prompt, the substitution, LM and output parsers appear to be separate abstractions having individual interfaces and responsibilities, the LangChain design introduces many interdependencies between them that can be poorly documented (leaky in some sense). Thus, when using the LCEL to craft an agent, the reusable components can be limited by the fact that their operations heavily depend on how other components work, and such dependencies are often entirely textual and not expressed in Python types,further complicating the matter.

In the field of Prompt Engineering, both LangChain and LlamaIndex provide enhanced functionality for executing textual prompt engineering. In addition to a substitution-based approach, LangChain supports some techniques for Prompt Optimization. This class of optimization can involve the selection of effective examples or the fine-tuning of various “hyper-parameters.” LangChain is also furnished with Example Selectors that utilize metrics such as similarity (possibly derived from a vector database), or simpler measures like n-gram overlap, to distill a subset of examples that may enhance the overall performance result. Nonetheless, this process is conducted independently from both the LLM and the prompting strategy itself. Furthermore, the Example Selectors require a substantial number of fully annotated examples to select a beneficial subset.

LangChain, as a prompting centric framework, has also developed an ecosystem for hosting prompts through its LangSmith platform. Prompts can be hosted in LangSmith to be shared with others. When leveraged in conjunction with LCEL and LangChain’s Agent and Chain abstraction, the prompts could be used to power interesting LLM interaction patterns through prompt reuse.

5) Open-Ended Agents/Pipelines

We categorize open-ended agent and multi-agent chat together in the final section due to their shared nature as frameworks operating at the agent systems level.

i) Open-Ended Agents/Pipelines

In addition to prepackaged utilities, LangChain is also equipped with off-the-shelf agent pipelines or “chains” that could be used to run sophisticated LM queries with diverse prompting strategies that works out-of-the-box. However, LangChain, compared to other frameworks like AutoGPT, lacks prebuilt pipelines that could invoke other external tools. In comparison, frameworks like AutoGPT, focus on building agent systems that require minimal human intervention to solve given tasks. Internally, the tool has access to a set of pre-existing tools (which may include calculators, internet access, local file access, etc.), a set of fixed prompts that drive the LM to perform its designated tasks, and fixed models of short-term and long-term memory. Whilst you can customize such tools for specific purposes, they are not designed to be extensible in the sense that you can easily substitute the pattern of prompting or integrate with existing programs conveniently. However, this is balanced by the convenience of an out-of-the-box solution that directly extends the base LM, integrating many tools to solve tasks efficiently.

Another tool worth noting in this category is MetaGPT, although this framework is of interest to other sections of the post. MetaGPT prides itself on the ability to generate a “one-line requirement” as input and outputs completed programs, research documents, etc. Internally, it assigns roles, such as Software Engineer, Project Manager, Architect, and QA, to different LM interaction contexts. Similar to AutoGPT, these roles have fixed prompts and capabilities built into the tool that are available out of the box. MetaGPT internally encodes a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) B4 were presenting some imaginary company driven to solve your task and uses this SOP as an “algorithm” to orchestrate the collaboration between different roles. MetaGPT allows for extensions through the addition of new roles and defining the prompt, capabilities, and its integration into the SOP. This is akin to the notion of plugins in AutoGPT.

BabyAGI also aims to utilize LMs to automatically perform a set of tasks. Essentially, LMs use available execution agents to orchestrate how tasks can be broken down into subtasks and how these subtasks should be completed.

ii) Multi-Agent Chat

AutoGen and MetaGPT are the two main frameworks that have abstractions over chatting and communicating between multiple agents with different roles and characteristics. In AutoGen, the base abstraction consists of the Assistant Agents, which are wrappers around LMs, and UserProxyAgents, which can execute code or interact with a human, allowing the agent system to interact with the outside environment. To facilitate the possibility of multiple agents interacting, a GroupChatManager can also be introduced to manage how the different chat agents are allowed to interact with each other. Therefore, given the ability to compose different agents, and their interactions, the library could support a variety of conversation patterns. MetaGPT takes a slightly different approach. At face value, it is just an automated tool for performing AI powered tasks, but at its core, it exposes interesting multi-agent abstraction. Conceptually, MetaGPT consists of a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) and a set of roles (which are akin to the agents in the AutoGen sense). The SOP contains instructions on managing how the different roles/agents could interact with one another and encapsulate the division of labor assigning broken down subtasks to the appropriate roles. A global environment with a shared knowledge and context is provided in the framework, where each role/agent could be specified to “subscribe” to a subset of this knowledge deemed relevant.

Conclusion

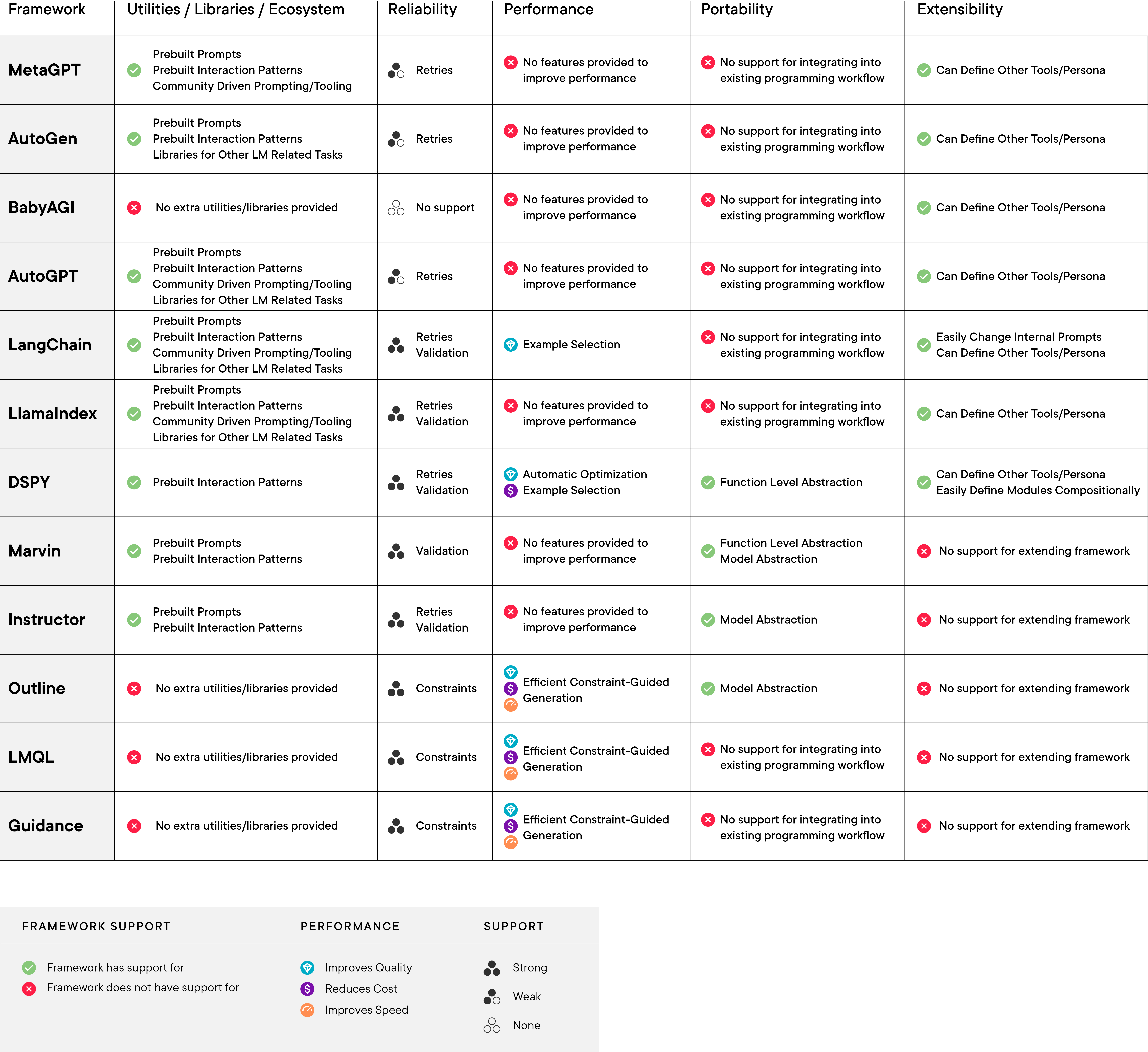

There has been significant development in recent months in the landscape of LLM programming abstractions leading a flourish of popular frameworks. We presented a 7-layer model of abstraction to classify the libraries evaluated and delineate the separation of concerns that we have observed. We then examined five categories of frameworks in terms of their intrinsic and extrinsic features. In particular, their intrinsic features include whether they can be easily extended, what kind of features they support to ensure reliable or stable outputs, and how they are structured so as to be able to interact with other libraries and frameworks. Extrinsic features include aspects of community and ecosystem, e.g., reusable prompting strategies, or libraries built on top of the framework that can be used for richer and more domain-specific tasks. To provide a bird’s eye view of these recent frameworks through the lens of these features and quality, we have laid out their respective utilities/libraries/ecosystem, reliability, performance, portability and extensibility, in Table 3. Further, in Figure 2 accompanying the table, we define and expand upon some of the terms used in Table 3.

We hope that this article will be helpful for developers and framework designers alike to paint a clear picture of existing work.

Figure 2 – Expansion of Terms Referenced in Table 3

Utilities/Libraries/Ecosystem

- What utility/tools does the library provide? Are there any community resources available for the library?

Reliability

- How does the framework seek to make the result of a LM-powered program more dependable?

Performance

- How does the framework perform in terms of cost, speed or quality of the generated content?

Portability

- How easy is it to integrate the library into an existing programming workflow?

Extensibility

- How easy is it to extend the functionality of the library?

Prebuilt Prompts

- Prompts, String template built into the framework to accomplish some preset tasks such as requesting the LM to output in a particular schema

Prebuilt Interaction Patterns

- Strategies like RAG, ReAct, Chain-of-thoughts, directly built-in to the frameworks. Prebuilt Interaction Patterns refer to predefined, ready-to-use structures, functions, or templates.

Community Driven Prompting/Tooling

- There is an active community driven effort to integrate prompts and tools to a particular framework

Retries

- Regenerating some output if it is unsatisfactory

Validation

- Validating the generated output against some criterion, commonly a schema

Constraints

- Limiting the output based on specific criteria to prevent the generation of any poorly formed or undesirable outputs.

Model Abstraction

- Abstracting the output of an LM as a data model that has some predefined schema

Function Level Abstraction

- Abstracting the LM as a callable function in a programming environment that has some predefined input and output parameters

Acknowledgements

This article benefitted greatly from feedback and suggestions provided by Larry Rudolph (Two Sigma), Chris Mulligan (Two Sigma), and Collin Jung (Stanford), to whom the authors offer our sincerest thanks.