Explicitly or implicitly, most of the world’s institutional investors hold a long position on China across their multi-asset class portfolios. In the face of this long exposure, the greater than 30 percent decline in China’s domestic equity market (A-shares) prices from June highs to early July lows raises some concerns but ought not inspire panic.1

While panic over the latest bout of volatility may be unwarranted – equity prices in China are still up 70 percent year over year – the Chinese government’s hyperactive response (e.g., lending money to brokerages to buy stocks, forbidding large shareholders from selling, allowing companies to suspend trading of their shares, speeding up infrastructure spending, and loosening monetary policy) seems more worrying. Global investors have experience managing the fallout from an equity bubble pop, but rarely do governments directly intervene in stock market crashes.

Three historical case studies may hint at eventual outcomes

In the absence of a richer data set covering such events, three brief historical case studies outline a range of potential outcomes from China’s unconventional stock market intervention.

- The first case study describes Hong Kong during August 1998, when the government sought to fend off the panic from a global financial crisis by propping up the Hang Seng Index via direct share purchases.

- The second case study describes Japan in August 1992, when the Japanese Ministry of Finance launched a “price keeping operation” to sustain a 17,000 floor underneath the falling Nikkei index.

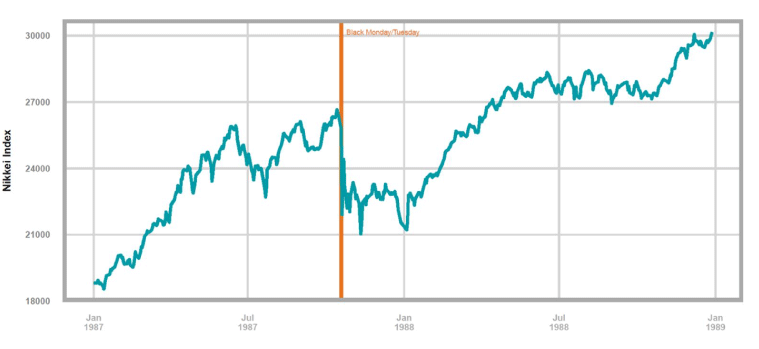

- The third case study also describes Japan but occurred a few years earlier. In October 1987, Japan responded to the Black Tuesday (Black Monday in New York) rout of global equity prices by “encouraging” brokers and institutional fund managers not to sell equities.

The Chinese government likely hopes the first case study proves the most analogous, while institutional investors likely dread the second scenario more. Yet along most dimensions, the third case study appears the most apropos.